The Forever Debate

Because Science is never "settled".

Imagine we set a camera up in such a way that an acre of meadow was in focus, and then snapped a frame every day for 6,000 years. At the end of this period, we compile the images into a film and roll it at 24 frames per second (the projection rate for 35 mm movies). If we all took our seats in the theater and watched the film, it would take about 25 days from beginning to end. The meadow would be a canvas on which life tumbled and changed. We’d see it covered with grass, or flowers, or trees in a constant ebb and flow. Forests would spring up and then vanish. There would be fires, and snowstorms, and then the inevitable eruption of life. Depending on the meadow chosen, buildings might appear and then vanish, and then be replaced by something else. The only constant would be change. The screen would be alive with motion, color, and activity. But here’s the thing: Each individual who watched the film would have different favorite parts. Some might prefer a flowering meadow. Others a forest. Some a small village, or a homestead, or a city.

From where I sit—63 years old and striving to be as objective as possible—looking back at the history I remember and the history I have read, humanity seems to shift and roil much like any natural process. We have precious little control over how this unfolds but we—all of us—harbor the delusion that we can freeze time and dictate outcomes to one degree or another. In 1968 I was ten years old and we lived in Brooklyn, Connecticut. The woods were our playground and we, the kids in the neighborhood, had names for the various places. There were The Pits, sandy dunes left behind when someone excavated about an acre of topsoil. There was the river (really, Blackwell’s Brook). There was The Dump, a pile of moldering debris beside an overgrown road near the rusting shell of a pickup that, once upon a time, had to be cranked by hand to start. Of course, that was more than fifty years ago and if I returned and walked those woods today, much will have changed. The truck will be gone and the road will have vanished. There will be houses on The Pits. Blackwell’s Brook still flows, but through a changed and changing landscape.

This is true of everything I have ever known—people, places, and things. It’s a hard truth: We can never revisited the moment we occupy, because everything is always in motion and changing. There is no permanence.

President Obama often spoke of being “on the right side of history”; or that others, particularly those who didn’t agree with him, were on the wrong side. In his first inaugural address, for example, President Obama said, “To those who cling to power through corruption and deceit and the silencing of dissent, know that you are on the wrong side of history.” This rhetorical jujitsu continues to be used and has no apparent boundaries, but history has no right side or wrong side. History simply is. It is what happened. About 3,300 years ago a battle was fought between the Egyptians under Ramses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River in what is now the Syrian/Lebanon border. It was a huge deal. 5,000 chariots were involved and more than 2,000 destroyed. No one knows how many died. Who, do you suppose, was on the “right side of history”? Shall we pull down the Nubian monuments because the Hittites were oppressed or because Egypt had slaves? Why not? What’s the time limit on outrage?

Recently the term “liberal” has fallen into disuse and “progressive” has found it’s way into conversation when people discuss the opposing poles of American politics. Generally speaking, we have a Right and a Left—the Right being Conservative and the left being, increasingly, Progressive. On paper, Progressivism sounds good, if ill conceived and poorly executed.

Personally, I’m a big fan of progress. I love air conditioning and hot water and eating ice cream while watching Netflix over my WiFi network. Dentistry has probably saved my life and has certainly contributed to the quality of the life I have. So the original Progressives had one thing right. Advancements in technology—in medicine, manufacturing, farming, and economics raise the quality of life for everyone. This is axiomatic.

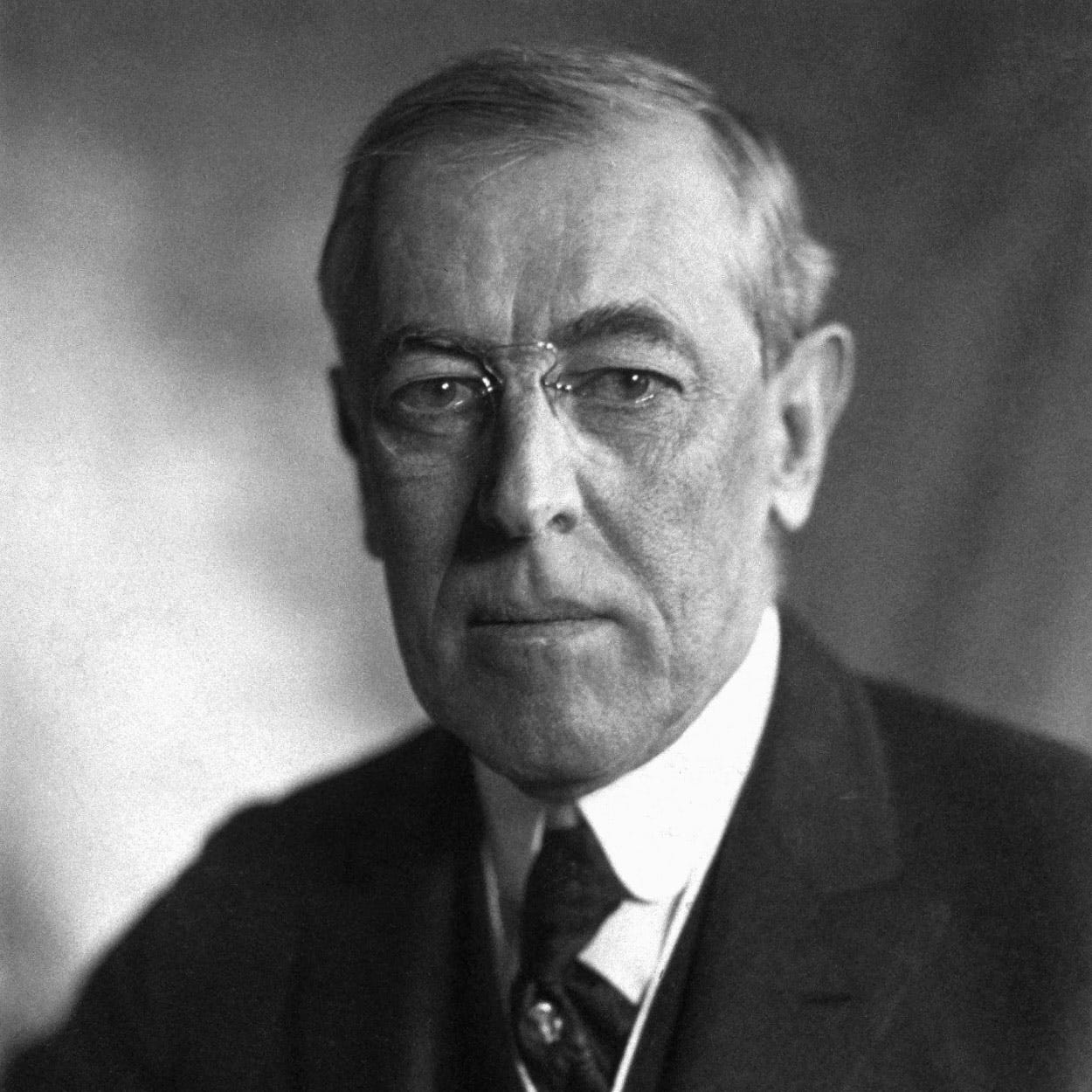

There is a disconnect, though, between Progress and Progressivism. Progressives believe that once a problem is identified (poverty, addiction, mental illness, inequality, environmental concerns, any problem at all), all that need be done is to employ the power of the government to empower experts to direct progress until the problem is solved. This seemed a little too goofy to me, so I took some time recently to read some of the early Progressives--John Dewey, Jane Adams, Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair, Woodrow Wilson and Teddy Roosevelt. Like any other -ism one chooses to consider, they were not entirely wrong. They were also not entirely correct. But they absolutely believe(d) in the power of Experts.

The thumbnail version of American history is that in response to abuses during the industrial revolution—child labor, environmental degradation, and food safety for example—it was assumed that the awesome power of the government should be used to correct these problems and curb the abuses for the common good. Teddy Roosevelt wrote, “There are, in the body politic, economic and social, many and grave evils, and there is urgent necessity for the sternest war upon them. There should be relentless exposure of and attack upon every evil man whether politician or business man, every evil practice, whether in politics, in business, or in social life.”

Hard to argue against this. At the time, early in the 1900s, monopolies were common, labor practices unfair, and food often unsafe (see: The Jungle). 1916 Woodrow Wilson, an avowed Progressive, won election on a platform that called for legislation providing for an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child labor, and safeguards for female workers. Hard to complain about any of that.

But it didn’t stop there. Like the old saw about every problem appearing, to a carpenter, as a nail, Progressives saw one tool—the power of the experts—as the solution to all of society’s ills. Real and imagined. And “evil” is a term that begs to be defined. Woodrow Wilson, for example, was, like Margaret Sanger, a believer in the “science” of race and eugenics. Humans breeding willy nilly were passing on their shortcomings to their offspring. Science could do a better job of this, if only people would do what the experts told them to do. This “scientific” racism was considered true and really only fell out of favor after Adolf Hitler. Wilson was a racist and an apologist for slavery, and specifically criticized efforts to protect voting rights for African-Americans and rulings by federal judges against state courts that refused to empanel black jurors. According to Wilson, Republican congressional leaders had acted out of idealism, displaying "blatant disregard of the child-like state of the Negro and natural order of life", thus endangering American democracy as a whole. Take note of “natural order of life”. Wilson believed that races were real, that some races were superior, that this was settle science, and that government should act accordingly.

And this is the rub. “Experts” are not the arbiters of good. To the Progressives, the principles upon which the nation was founded—individual liberty, the natural rights of man, and the constraints placed upon the government—were impediments. The ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence and The Constitution were old fashioned, good for their time, but by the 19-teens, more than a century after the founding, outdated and to be reconsidered. They could not be trusted when the science indicated otherwise.

This debate has continued to this day. Choose your Science carefully, and your experts more carefully still.

Mileage may vary.

Peace.

Was thinking of you today. Praying all is well. ❤️

Your FB friend,

Heidi Westby.